![[object Object]](https://admin.thus.ph/uploads/MAGELLAN_COVER_3b21474555.jpg)

How Ferdinand Magellan—Survivor of Numerous Challenges—Died Because of Philippine Politics

A classic case of "fuck around and find out."

Thus

2025-04-27T10:44:59.611Z

During his attempt to circumnavigate the world, the famed explorer Ferdinand Magellan survived numerous challenges except one: Philippine politics.

Of course, it wasn’t known to be that before. During his expedition, the group of islands now known as the Philippines was still just a collection of territories ruled by various tribal leaders. Power struggles tended to happen among these groups and Magellan didn’t just get caught up in one of them; he caused it and paid the price.

In 1521, the Portuguese explorer was in the midst of an expedition meant to help Spain find a western sea route to the Moluccas, a now-Indonesian territory once known as the Spice Islands. During his journey, his crew suffered casualties due to scurvy, he faced two mutinies, and severe storms threatened to end his journey. But none of them were enough to stop the man who was on his way to be the first person to lead a circumnavigation the world. But then, he found himself in a group of islands now known as the Visayas region of the Philippines. And he never left it alive.

This is partly because of his ties with Rajah Humabon—the ruler of Cebu whom he met soon after he arrived in the region in April. According to Antonio Pigafetta, the scholar who joined Magellan’s expedition, the explorer developed close ties with the Asian chief (whom they referred to as a king.) They exchanged gifts with each other and both entered a blood compact: a ritual which can be interpreted as a sign of friendship. Participants mix their blood into liquid (like wine) and drink it.

The ties between the two men deepened further when Magellan’s group managed to convince Humabon, his wife and his subjects to convert to Christianity; to burn their idols and put a cross in its place. The priest accompanying their voyage, Pedro de Valderrama, baptized them and christened Humabon, “Don Carlos Valderrama,” after King Charles I of Spain. Pigafetta saw this unfold.

“The captain [Magellan] told the king [Humabon] through the interpreter that he thanked God for inspiring him to became a Christian,” Pigafetta wrote. “[Now] he would more easily conquer his enemies than before.”

Magellan then said that he will go back to Spain and eventually return to Humabon with more men to bolster the latter’s forces and make him the greatest king in “those regions” since he was the first to express the desire to become a Christian. This promise of expansion, however, had impediments. Humabon, after all, was not the only ruler of the region.

In the nearby island of Mactan, there were two other chieftains. The first was Zula, a man who didn’t become a problem for Magellan since he soon pledged his allegiance to the Spanish host and, consequently, the Spanish crown. He sent one of his sons to present two goats to Magellan and promised to send more gifts to the explorer. This, however, didn’t happen the attempt was blocked by another Mactan ruler: a man named Lapu-Lapu.

Lapu-Lapu refused to swear fealty to the Spaniards. His tribe also refused conversion to Christianity and he refused to pay tribute to the foreigners.

To impress his allies, Magellan told Humabon that he will subdue Lapu-Lapu. He even showed how he intended to do it by flexing medieval armaments. He had a man don European gear, stand in the middle of three to be struck by swords and daggers that did little-to-no damage. This left Humabon and his men impressed.

It also emboldened Magellan; he was so confident that on April 27, 1521, when he faced Lapu-Lapu’s tribe of around 1,500 fighters, he did so with only 49 men.

“The Christian king [Humabon] would have aided us,” Pigafetta wrote. “But the captain charged him before we landed, not to leave his [ship,] but to stay to see how we fought.”

Humabon did just that; Zula did too. And from their ships, they saw just how formidable their fellow natives were.

According to Pigafetta, Megallan first sent a message to Lapu-Lapu’s tribe saying that if they continued to refuse the authority of the Spanish king and pay them tribute, they would demonstrate just how effective their European weapons were in battle. Lapu-Lapu contingent was quite unmoved. In response, they merely asked Magellan’s crew to wait until sunrise before attacking, and the European obliged.

The sun rose eventually. And not long after, Magellan, referred to by Pigafetta’s memoir as their expedition’s “light” fell.

The Battle of Mactan

When the battle began, the natives formed three divisions. They charged down upon the meager Spanish host with loud cries. The Spanish contingent fired their muskets upon Lapu-Lapu’s troops, and they responded with arrows and bamboo spears, some tipped with iron according to Pigafetta. They also exhibited adaptability in battle by firing at the legs of the invaders when they realized their vulnerability since they weren’t covered in armor.

Magellan soon found his troops overwhelmed so he ordered the houses of the natives burned, hoping to distract them. However, this merely enraged Lapu-Lapu’s people. Two of Magellan’s men were killed near the houses, and Magellan was shot through the right leg with a poisoned arrow.

“On that account, he ordered us to retire slowly,” Pigafetta said. “But the men took to flight, except six or eight of us who remained with the captain.”

The Spanish contingent was pushed back onto the shore, forcing them to fight mostly with their knees deep in water. Pigafetta wrote that Megallan kept getting his helmet knocked off his head, but he always stood firm “like a good knight.”

“Thus did we fight for more than one hour,” he wrote, “refusing to retire farther.”

The chronicler recalled that Magellan used his lance to kill a native, but eventually, one of them managed to wound the Portuguese with a sword that Pigafetta likened to a scimitar, “but only larger.” He fell, and natives swarmed him while the rest of his surviving men managed to escape to their boats.

“They killed our mirror,” Pigafetta wrote, “our light, our comfort, and our true guide.”

Others died after him.

Following the battle, Humabon betrayed the remaining members of Magellan’s crew. He had a number of them poisoned during the feast. According to Pigafetta, this happened because Enrique of Malacca, the Malay translator acquired by Magellan as a slave. Magellan once willed that Enrique would be free upon his death, but Duarte Barbosa, Magellan’s immediate successor, refused. This allegedly urged him to warn Humabon that the Spaniards plan to capture the latter.

Meanwhile, 16th century historian Fernão de Oliveira gave a different story based on the account of a mariner in Magellan’s expedition. According to the mariner, Lapu-Lapu apparently warned Humabon that he would be “destroyed” if the latter did not side with the former who was victorious in the Battle of Mactan. Humabon supposedly chose to do so, thereby betraying the remaining Spaniards.

For whatever reason, Humabon’s betrayal saw the surviving Spaniards escape, leaving behind the idea of a Christianity in the islands now known as the Philippines since no one was left there to sustain it. It would take about 44 more years before it returned and got fully integrated into Philippine society.

But even after that, even after the Spaniards took control over much of the country, its learnings and its history, Magellan is remembered in the Philippines now as a man who was killed for trying to invade Philippine soil, the villain in Lapu-Lapu’s story of heroism and defiance, an explorer who traveled far and overreached.

Of course, it wasn’t known to be that before. During his expedition, the group of islands now known as the Philippines was still just a collection of territories ruled by various tribal leaders. Power struggles tended to happen among these groups and Magellan didn’t just get caught up in one of them; he caused it and paid the price.

In 1521, the Portuguese explorer was in the midst of an expedition meant to help Spain find a western sea route to the Moluccas, a now-Indonesian territory once known as the Spice Islands. During his journey, his crew suffered casualties due to scurvy, he faced two mutinies, and severe storms threatened to end his journey. But none of them were enough to stop the man who was on his way to be the first person to lead a circumnavigation the world. But then, he found himself in a group of islands now known as the Visayas region of the Philippines. And he never left it alive.

This is partly because of his ties with Rajah Humabon—the ruler of Cebu whom he met soon after he arrived in the region in April. According to Antonio Pigafetta, the scholar who joined Magellan’s expedition, the explorer developed close ties with the Asian chief (whom they referred to as a king.) They exchanged gifts with each other and both entered a blood compact: a ritual which can be interpreted as a sign of friendship. Participants mix their blood into liquid (like wine) and drink it.

The ties between the two men deepened further when Magellan’s group managed to convince Humabon, his wife and his subjects to convert to Christianity; to burn their idols and put a cross in its place. The priest accompanying their voyage, Pedro de Valderrama, baptized them and christened Humabon, “Don Carlos Valderrama,” after King Charles I of Spain. Pigafetta saw this unfold.

“The captain [Magellan] told the king [Humabon] through the interpreter that he thanked God for inspiring him to became a Christian,” Pigafetta wrote. “[Now] he would more easily conquer his enemies than before.”

Magellan then said that he will go back to Spain and eventually return to Humabon with more men to bolster the latter’s forces and make him the greatest king in “those regions” since he was the first to express the desire to become a Christian. This promise of expansion, however, had impediments. Humabon, after all, was not the only ruler of the region.

In the nearby island of Mactan, there were two other chieftains. The first was Zula, a man who didn’t become a problem for Magellan since he soon pledged his allegiance to the Spanish host and, consequently, the Spanish crown. He sent one of his sons to present two goats to Magellan and promised to send more gifts to the explorer. This, however, didn’t happen the attempt was blocked by another Mactan ruler: a man named Lapu-Lapu.

Lapu-Lapu refused to swear fealty to the Spaniards. His tribe also refused conversion to Christianity and he refused to pay tribute to the foreigners.

To impress his allies, Magellan told Humabon that he will subdue Lapu-Lapu. He even showed how he intended to do it by flexing medieval armaments. He had a man don European gear, stand in the middle of three to be struck by swords and daggers that did little-to-no damage. This left Humabon and his men impressed.

It also emboldened Magellan; he was so confident that on April 27, 1521, when he faced Lapu-Lapu’s tribe of around 1,500 fighters, he did so with only 49 men.

“The Christian king [Humabon] would have aided us,” Pigafetta wrote. “But the captain charged him before we landed, not to leave his [ship,] but to stay to see how we fought.”

Humabon did just that; Zula did too. And from their ships, they saw just how formidable their fellow natives were.

According to Pigafetta, Megallan first sent a message to Lapu-Lapu’s tribe saying that if they continued to refuse the authority of the Spanish king and pay them tribute, they would demonstrate just how effective their European weapons were in battle. Lapu-Lapu contingent was quite unmoved. In response, they merely asked Magellan’s crew to wait until sunrise before attacking, and the European obliged.

The sun rose eventually. And not long after, Magellan, referred to by Pigafetta’s memoir as their expedition’s “light” fell.

The Battle of Mactan

When the battle began, the natives formed three divisions. They charged down upon the meager Spanish host with loud cries. The Spanish contingent fired their muskets upon Lapu-Lapu’s troops, and they responded with arrows and bamboo spears, some tipped with iron according to Pigafetta. They also exhibited adaptability in battle by firing at the legs of the invaders when they realized their vulnerability since they weren’t covered in armor.

Magellan soon found his troops overwhelmed so he ordered the houses of the natives burned, hoping to distract them. However, this merely enraged Lapu-Lapu’s people. Two of Magellan’s men were killed near the houses, and Magellan was shot through the right leg with a poisoned arrow.

“On that account, he ordered us to retire slowly,” Pigafetta said. “But the men took to flight, except six or eight of us who remained with the captain.”

The Spanish contingent was pushed back onto the shore, forcing them to fight mostly with their knees deep in water. Pigafetta wrote that Megallan kept getting his helmet knocked off his head, but he always stood firm “like a good knight.”

“Thus did we fight for more than one hour,” he wrote, “refusing to retire farther.”

The chronicler recalled that Magellan used his lance to kill a native, but eventually, one of them managed to wound the Portuguese with a sword that Pigafetta likened to a scimitar, “but only larger.” He fell, and natives swarmed him while the rest of his surviving men managed to escape to their boats.

“They killed our mirror,” Pigafetta wrote, “our light, our comfort, and our true guide.”

Others died after him.

Following the battle, Humabon betrayed the remaining members of Magellan’s crew. He had a number of them poisoned during the feast. According to Pigafetta, this happened because Enrique of Malacca, the Malay translator acquired by Magellan as a slave. Magellan once willed that Enrique would be free upon his death, but Duarte Barbosa, Magellan’s immediate successor, refused. This allegedly urged him to warn Humabon that the Spaniards plan to capture the latter.

Meanwhile, 16th century historian Fernão de Oliveira gave a different story based on the account of a mariner in Magellan’s expedition. According to the mariner, Lapu-Lapu apparently warned Humabon that he would be “destroyed” if the latter did not side with the former who was victorious in the Battle of Mactan. Humabon supposedly chose to do so, thereby betraying the remaining Spaniards.

For whatever reason, Humabon’s betrayal saw the surviving Spaniards escape, leaving behind the idea of a Christianity in the islands now known as the Philippines since no one was left there to sustain it. It would take about 44 more years before it returned and got fully integrated into Philippine society.

But even after that, even after the Spaniards took control over much of the country, its learnings and its history, Magellan is remembered in the Philippines now as a man who was killed for trying to invade Philippine soil, the villain in Lapu-Lapu’s story of heroism and defiance, an explorer who traveled far and overreached.

Recommended

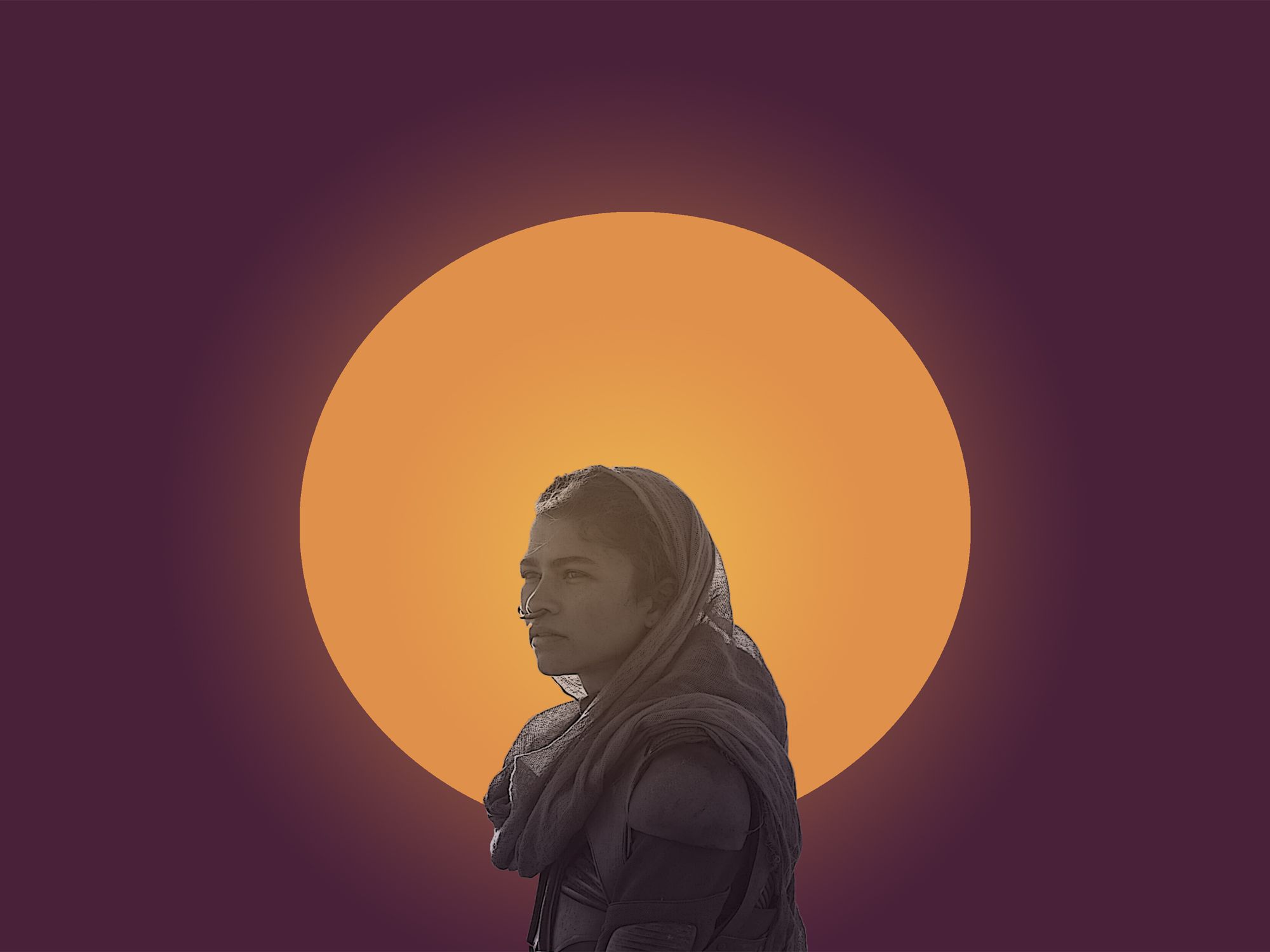

How the Women of “Dune: Part Two” Added Spice to the Series

Karl R. De Mesa

How Civilian Group "Atin Ito" Hopes to Turn the Tide at the West Philippine Sea

Angelo Cantera

Why Crime Novelist Ronaldo Vivo Jr. Put "Skeletons" in "God's Garden"

Karl R. De Mesa

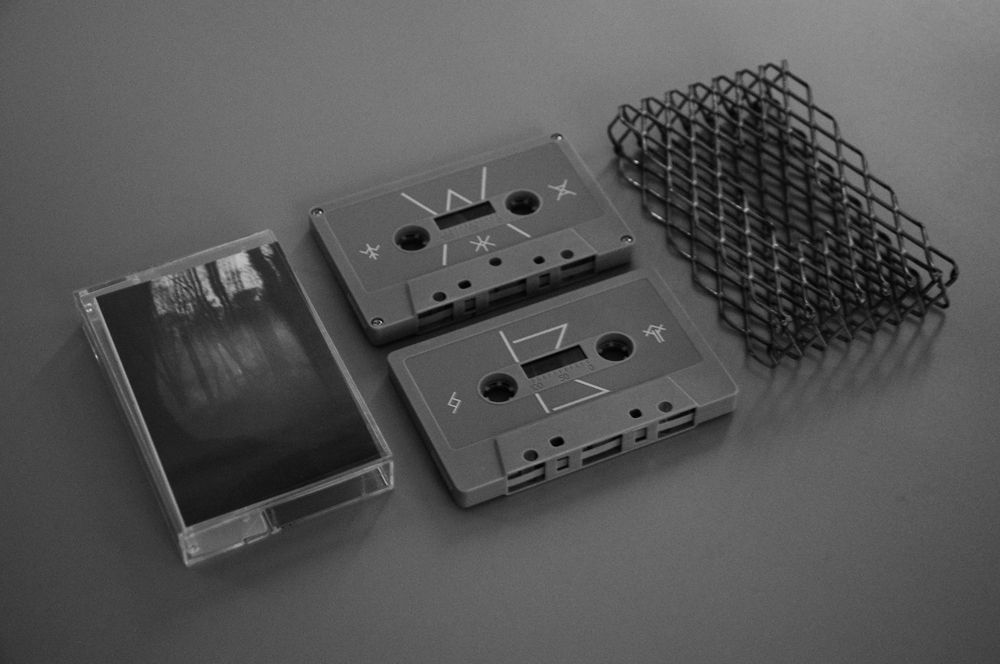

PJ Ong: The Cebuano Designer Unleashed Upon the World After He Caged Cassette Tapes

Karl R. De Mesa

Why Workplace Inclusivity Works

Angelo Cantera

How You Can Help Prevent Suicide

Thus